My Stars —

2003, two-channel video installation, wall mural, mirrored kaleidoscopes, 5:30 minutes (excerpt 1:30 minutes)

-from curator Cassandra Coblentz’ catalog essay for SurfaceTension,

an exhibition at The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, 2003

Her newly redesigned installation brings together two video works National and International that explore/mine two vacant architectural spaces. Absent any human protagonists, the monumental buildings are the unlikely stars of Hironaka’s videos.

The first video, subtitled National, documents the interior of Philadelphia’s landmark Modernist National Product’s building. Now deserted, Hironaka’s camera traverses its corridors, uncovering vacant offices that the artist has constructed to appear as if its inhabitants fled suddenly leaving behind open drawers and cabinets, boxes packed with paper work, and once fashionable modernist furniture. From one space to the next the camera fixes on bizarre and seemingly forgotten and slightly ominous scenes: a restroom trash bin overflowing with paper towels; a pile of brightly colored futon mattresses. The second video, subtitled International, was filmed inside the equally monumental Fabrica building designed by Tadao Andono, situated outside Treviso in Northern Italy. Though far from derelict, this building is no less vacant than its Philadelphia counterpart, inhabited only by anonymous caretakers who maintain its polished finish. Hironaka’s camera follows the building’s contours, tracing the vertical plains of white walls and the repeating rectangles of a slightly spiraling staircase. Probing the space as if searching for some lingering trace of human presence, the lens gleans only subtle shadows and patterns of light filtered through the building’s geometric architectural forms.

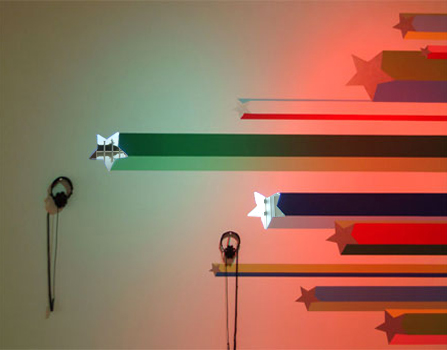

The installation embeds these video works within a tableau that consists of a wall painting, two star-shaped incisions in the surface of the gallery wall and two star-shaped mirrored kaleidoscopic structures that form a bridge between the surface of the gallery wall and two monitors that present the videos recessed within the wall. The star-shaped cuts are situated among other silver painted stars in the design of the wall painting. As if depicting the horizontal movement of shooting stars, brightly colored bands extend from not only the painted stars but also from the cut out stars and the moving imagery of the kaleidoscopic screen. From inside the gallery wall, the mirrored planes of the kaleidoscope infinitely morph the geometric forms and colors depicted in the videos. These forms and colors seem to spill out onto the surface of the gallery wall in such a way that architectural space becomes a no less malleable formal element than digital video. The wall painting even further emphasizes the shifts between planes of surface and depth, because it establishes a flat static surface that provides a contrast to the dynamic active moving imagery within the wall.

The distorting lens of the kaleidoscopes results in a visual experience of endlessly unfolding spaces. Reflected and refracted off the mirrored plains, surfaces/shapes seem to constantly un/fold into depth, and any notion of a “point of view” as constructed by the camera is fractured beyond recognition. One might say that Hironaka fractures the “screen-as-eye” to reveal the underlying heterogeneity of the moving image, a phenomenon, as Deleuze describes it, is “made up of breaks and disproportions, deprived of all centers, addressing itself as such to viewers who are no longer the center of their own perception.”

For Deleuze, the camera is not an instrument that is continuous with the human eye: it is, rather, an artificial mode of perception that transcends the limits of ordinary seeing. By contrast, it is the screen that functions as a surrogate eye, processing the plurality of visual data as image. “The eye isn’t the camera,” Deleuze writes, “it’s the screen. As for the camera, with all its propositional functions it’s a sort of third eye, the minds eye.” As Hironaka’s camera navigates these deserted spaces in real-time, it is constantly interrupted by rapidly edited sequences—flash-backs or visual memories of preceding rooms and architectural forms—flashes of what Deleuze calls the mind’s eye.

Hironaka uses audio and visual editing techniques not only to further the play of surface and depth, but also to reference memory and cinematic history. In both video works, Hironaka repeats and remixes sound bytes from historic Hollywood films to trope the cinematic convention of setting a tone through a soundtrack. Sounds, some gleaned from 60′s sci-fi films, such as: footsteps, clicks, white noise, and other abstract mechanical sounds, provide an aural echo of Hironka’s video editing. This coordinated sense of visual and aural rhythm establishes a keen sense of texture that contributes significantly to the overall tone of the work. In the realm of the visual, Hironaka’s explicit use of digital editing further emphasizes a very conscious construction of framing, often taking advantage of digital editing technology to frame one shot inside of another, or position two images of architectural spaces side by side within one framed shot. In a sense the entire work is a constantly repeating process of framing and reframing.